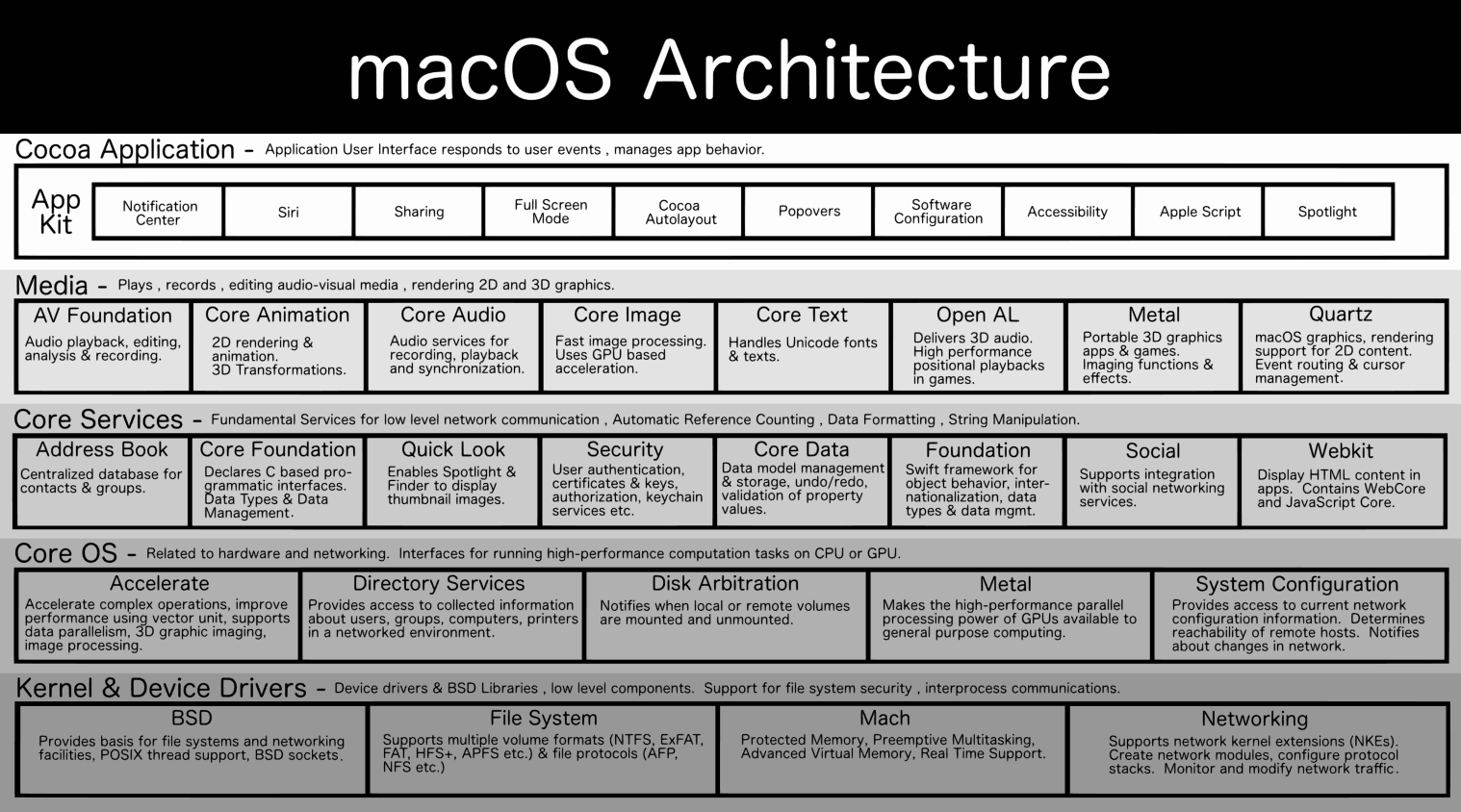

- MacOS Architecture

- Apple Properity File System (APFS)

- System Volume Protection

- Firmlinks

- PLIST Files

- Bundles

- Dyld

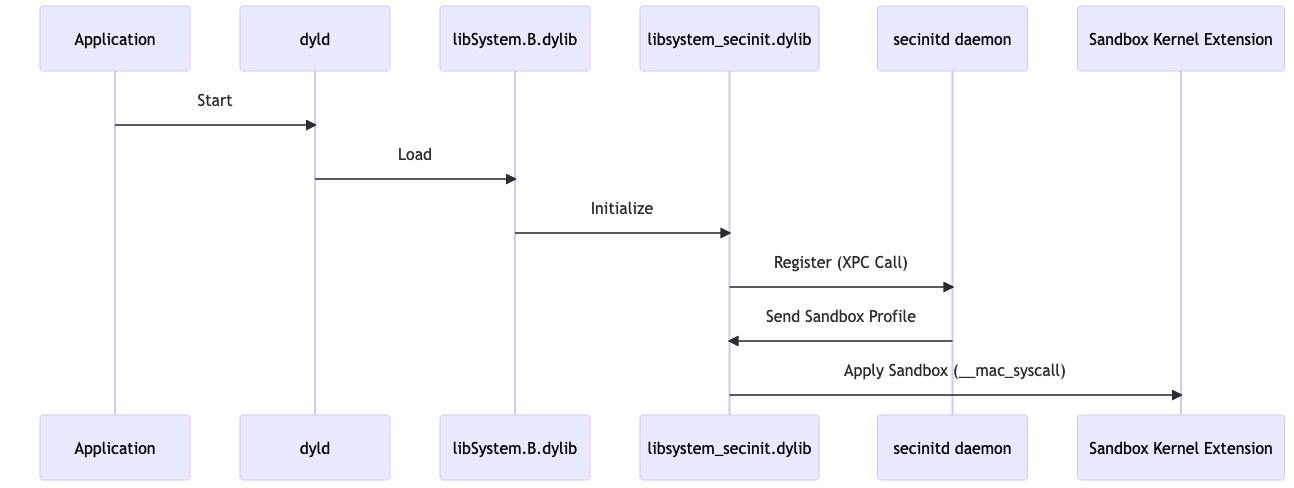

- Step 1: Load the Executable into the Debugger

- Step 2: Set a Breakpoint on xpc_pipe_routine

- Step 3: Run the Application

- Step 4: Check the Backtrace

- Step 5: Continue Execution and Break Again

- Step 6: Inspect the XPC Message

- Step 7: Step Out and Inspect the Reply

- Step 8: Set a Conditional Breakpoint on __mac_syscall

- Step 9: Continue and Modify Execution

- Step 10: Verify Execution

By Zeyad Azima

MacOS Architecture

Introduction

1. Application Layer

- AppKit: Facilitates the creation of desktop application interfaces, handling events, drawing operations, and user interface elements like buttons and text fields. For example, when you create a new document in TextEdit, AppKit is responsible for displaying the window, text editing area, and menu options.

- Notification Center: Manages the centralized delivery of notifications to the user. For example, when you receive a new email, Notification Center displays a pop-up message or updates an icon badge.

- Siri: Allows voice interaction with applications and system functions. For example, you can ask Siri to send a message, set reminders, or launch applications.

- Sharing & Full Screen: Supports easy content sharing to other applications or services and manages applications in full-screen mode. For example, using the Share button in Safari to post a webpage link to Twitter.

- Auto Layout: Dynamically calculates the size and position of all the views in your window based on constraints. For example, ensuring a button stays at the bottom right corner of a window, regardless of window size changes.

- Popovers & Configuration: Handles transient views that appear above other content, and manages application configurations. For example, a settings popover in Mail that allows adjusting mail sorting preferences.

2. Media Layer

- AV Foundation: Manages and plays audio-visual media. For example, playing a video file in QuickTime Player.

- Core Animation: Provides fluid animation for user interface elements. For example, smooth transitions when you minimize a window or open Mission Control.

- Core Audio: Handles audio operations system-wide. For example, managing audio streams and volume control across all running applications.

- Core Image: Used for high-performance image processing, which allows quick filtering and effects in applications like Photos.

- Core Text: Manages text layout and font rendering; crucial for reading and editing text in any app that displays large amounts of text.

- Metal: Optimizes graphics and compute operations by leveraging the GPU. For example, accelerating graphics rendering in games or graphical applications.

3. Core Services

- Address Book: Stores and retrieves user contact information. For example, when a user saves a new contact in the Contacts app, it is stored in the Address Book database.

- Core Foundation: Provides fundamental data types and collections, like strings and arrays, crucial for app development. For example, managing data structures in any app.

- Quick Look: Allows users to preview documents or images quickly without opening them in a dedicated app, like previewing PDF files in Finder.

- Social: Provides frameworks to integrate with social media platforms. For example, sharing images directly from Preview to Facebook.

- Webkit: Powers the Safari browser; handles HTML content rendering and JavaScript execution.

4. Core OS

- Accelerate: Optimizes large-scale mathematical computations, improving performance in scientific and financial software.

- Directory Services: Manages user accounts and permissions. For example, when logging in, Directory Services verifies user credentials.

- Disk Arbitration: Manages access to disk volumes to prevent file system corruption. For example, it ensures that a disk is not ejected while files are being written to it.

5. Kernel & Device Drivers

- BSD: Provides networking, security, and file system support. For example, BSD sockets are used for network communication in apps like Mail and Safari.

- Mach: The core around which macOS is built, handling low-level tasks like memory management and process scheduling. For example, Mach allocates memory when you open an app and schedules CPU time for it to run.

- Networking & Security: Includes components that handle secure network communications and data encryption. For example, establishing encrypted connections over Wi-Fi.

- File System Management: The file system manages the storage of data in an organized manner so that it can be easily accessed, modified, and managed. It handles operations such as reading, writing, creating, and deleting files and directories.

System Directories

POSIX Directories

/bin, /usr/bin: Contains essential user-executable binaries like shell commands and utilities./sbin, /usr/sbin: Holds system administration binaries essential for system maintenance and operations./usr/lib: Stores dynamic libraries (.dylibs) that provide functionality for multiple applications./tmp: A temporary directory, cleared at reboot, with a sticky bit set to prevent deletion of files by non-owners./var: Includes logs, configuration files, and user-specific temporary files. Root’s home directory is/var/root.

macOS Directories

/Applications: Standard location for user-installed applications accessible to all users./System: Contains macOS’s core components, like system files and libraries, protected by System Integrity Protection (SIP)./Users: Home directories for all users, with personal files, settings, and documents./Library: Stores system-wide application support files and libraries./System/Applicationsand/System/Cryptexes/App/System/Applications: Host core system applications, with certain apps in a secure cryptex for added security.

Launch Agents and Daemons

/System/Library/LaunchDaemons,/System/Library/LaunchAgents: System-level agents and daemons that execute automatically./Library/LaunchDaemons,/Library/LaunchAgents: For third-party daemons and agents that run at startup or login.~/Library/LaunchAgents: User-specific agents that auto-run at user login.

Application Data and Support

/Library/Application Support: Contains application support files and data for applications running as root.~/Library/Application Support: User-specific application support files and data.~/Library/Containers: Sandboxed applications are stored here, with strict filesystem access limitations.

Frameworks and Extensions

/System/Library/Frameworks,/System/Cryptexes/OS/System/Library/Frameworks: Home to system frameworks used by applications./System/Library/PrivateFrameworks,/System/Cryptexes/OS/System/Library/PrivateFrameworks: Contains private frameworks not for public use, restricted from Mac App Store applications./Library/Extensions,/System/Library/Extensions: Locations for kernel extensions (KEXTs), including third-party extensions.

Special and Security Directories

/Library/PrivilegedHelperTools: Where third-party daemons that need root privileges reside./usr/bin,/usr/sbin,/bin,/sbin: Core system binaries for both user commands and system administration./private: Contains sensitive directories such as/private/etc,/private/var, and/private/tmpthat manage configuration, variable data, and temporary files.

Kernel and Kernel Extensions

/System/Library/Kernels/kernel: The location of the macOS kernel./System/Library/Extensions,/System/Cryptexes/OS/System/Library/Extensions: Directories for Apple’s kernel extensions.

Apple Properity File System (APFS)

The Apple File System (APFS) is an advanced file system introduced by Apple with macOS High Sierra in 2017. It was designed to replace the older Hierarchical File System Plus (HFS+) to better accommodate the modern storage technologies and to enhance performance, reliability, and scalability. APFS operates on the concept of containers and volumes. A single APFS container can house multiple volumes that share the container’s free space. Volumes under APFS are flexible and can grow and shrink dynamically, unlike traditional partitions. This adaptability is crucial for devices with limited storage capacities like mobile devices.

- Check disk:

diskutil list |

- Output:

/dev/disk0 (internal, physical): |

/dev/disk0: This represents the physical disk.disk0is usually the primary hard drive.GUID_partition_scheme: The partition layout used, suitable for both Intel-based and ARM-based Macs.EFI: A small partition that contains boot files.Apple_APFS Container disk1: AnAPFScontainer that spans nearly the entire disk.

/dev/disk1(synthesized): This is theAPFScontainer synthesized view, showing volumes within the container.APFS Container Scheme: Shows thatdisk1is an APFS container.Physical Store disk0s2: Indicates that this container is located ondisk0s2.APFSVolumes (Macintosh HD,Preboot,Recovery,VM): These are logical volumes within theAPFScontainer, each serving different purposes like system storage, boot management, system recovery, and virtual memory respectively.

System Volume Protection

macOS leverages several robust mechanisms to safeguard its core system files, primarily through System Integrity Protection (SIP), also known as rootless mode. SIP‘s primary function is to prevent modifications to crucial system files and directories, even by the superuser (root).

System Volume Protections in macOS

macOS employs robust mechanisms like System Integrity Protection (SIP), also known as rootless mode, to protect its core system files. SIP’s primary role is to prevent unauthorized modifications to critical system files and directories, even by the superuser (root).

Using ls with SIP Protection Flags

Using the ls -lO command can reveal which directories are protected by SIP:

- Check directories are protected by SIP:

user@mac ~ % ls -lO / |

Output:

total 0 |

The restricted flag denotes that the directory is protected under SIP, preventing any modifications. The sunlnk and hidden flags indicate directories with special attributes but not necessarily SIP protection.

Using diskutil to Explore APFS Configurations

Command:

diskutil apfs list |

Output:

APFS Container (1 found) |

- Data Volume: User-accessible files, non-critical system files.

- System Volume: Core system files, not mounted directly but

Verifying System Integrity and Cryptographic Seals

macOS further secures system integrity through cryptographic seals, which can be checked using csrutil:

Command:

csrutil authenticated-root status |

Output:

Authenticated Root status: enabled |

This confirms that the system’s root volume is cryptographically authenticated, ensuring that the core system files are untouched and secure from alterations.

Mounted File System Attributes

Command:

user@mac ~ % mount |

Output:

/dev/disk1s4s1 on / (apfs, sealed, local, read-only, journaled) |

- Sealed: The system volume is cryptographically sealed to prevent tampering.

- Read-only: The root volume is mounted as read-only to ensure no changes can be made during normal operation, reinforcing its integrity.

- Journaled: This attribute helps protect the integrity of the file system by keeping a continuous log (journal) that tracks changes to the file system.

Cryptexes: CRYPTographically-sealed EXtensions

Introduced in macOS Ventura, Cryptexes represent a novel approach to handling system updates and security Cryptexes are signed disk images that contain system files or applications and can be updated independently of the system.

Command Checking Cryptexes:

user@mac ~ % ls -l /System/Cryptexes |

Output:

lrwxr-xr-x 1 root wheel 42 Oct 18 05:36 App -> ../../System/Volumes/Preboot/Cryptexes/App |

These links show that Cryptexes are not traditionally mounted within the regular file system structure visible to the user, highlighting their specialized role and enhanced security measures.

Firmlinks

Firmlinks are a special type of symbolic link used by macOS to seamlessly integrate the read-only system volume with the writable data volume. This allows the operating system to maintain a clear separation between system files (which need to be protected from modifications to ensure system integrity) and user data (which needs to be freely writable by the user).

- Check Firmlinks:

cat /usr/share/firmlinks |

- Output

/AppleInternal AppleInternal |

On the left is the directory path on the System volume, and on the right, Is the directory path where it maps on the Data volume.

- Confirm directory with

inode:

On System volume |

PLIST Files

Convert Binary plist:

Convert to xml |

Bundles

Bundles are .app bundle, but many other executables are also packaged as bundles, such as .framework and .systemextension.

Dyld

Extract dyld-cache:

dyld-shared-cache-extractor /System/Volumes/Preboot/Cryptexes/OS/System/Library/dyld/dyld_shared_cache_{arch} /tmp/libraries |

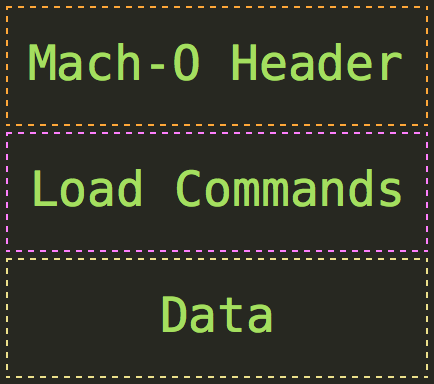

Mach-O File Format

The main 3 parts of Mach-o Fiel format:

Introduction

The Mach-O file format is the native executable format for macOS and iOS operating systems. Standing for Mach Object, the Mach-O format supports executable files, shared libraries, dynamically-loaded libraries, and object code for macOS. The design of this file format is heavily influenced by its focus on performance and the compatibility with the Mach kernel, which is part of the XNU kernel that powers Apple’s operating systems.

- Check File:

zeyad@azima% file /bin/pwd |

Universal Binaries

Universal binaries, also known as fat binaries, are unique to the Mach-O format. These binaries contain code for multiple architectures (like x86_64 and ARM) in a single file. This capability allows developers to build applications that can run on different types of hardware without the need for separate executables. The structure of a universal binary is essentially a container that includes multiple Mach-O files, each optimized for a specific processor architecture.

Mach-O Header

The Mach-O header is the starting point of any Mach-O file. It contains essential metadata about the file, such as the type of file (executable, object file, shared library), its architecture (ARM, x86_64, etc.), and the number of load commands. The header plays a crucial role in how the operating system processes and handles the Mach-O file during loading and execution.

Dump the Mach-O Header information using otool

otool -arch {x86_64/arm64e} -hv /path_to_binary |

Mach-O LOAD Command

Load commands within a Mach-O file instruct the loader on how to map the file’s contents into memory. These commands are vital for the dynamic linker to resolve symbols and connect dynamic libraries at runtime. Typical load commands include specifying the entry point of the executable, required dynamic libraries, and segment information such as the location and permissions of different sections of the file, There are around 50 type of load commands, But the most common ones:

LC_SEGMENT_64: This command is used to define a segment of memory that includes one or more sections. Each segment can contain executable code, data, or other resources needed by the executable or library. This command is specifically for

64-bitarchitectures.LC_LOAD_DYLINKER: This command specifies the dynamic linker (

dyld) that the system uses to load and link the shared libraries required by the executable at runtime. This is essential for resolving the dynamic dependencies of the application.LC_MAIN: Introduced with the newer

Mach-Ofile formats, this command points to the entry point of the main function, replacing the older entry point mechanism used in earlier versions. It specifies where the execution of the program begins.LC_LOAD_DYLIB: This command provides the paths to the dynamic libraries (

dylibs) that the executable depends on. These libraries are loaded by the dynamic linker during the execution of the application.LC_CODE_SIGNATURE: This command contains the offset and size of the code signature used by the operating system to verify the integrity and origin of the code in the Mach-O file. This is crucial for security purposes, ensuring that the code has not been tampered with.

- Dump load command with

otool:

otool -lv /path_to_binary |

- Dump libraries in

LC_LOAD_DYLINKER:

otool -L /path_to_binary |

Mach-O Data

The data in Mach-O files is organized into segments and sections. Segments are larger chunks of data with specific roles, like containing internal & external functions information, symbol table, executable code or read-only data. Each segment can be further divided into sections that hold smaller, more specific blocks of data. This hierarchical structure allows for efficient data management and access, crucial for performance during execution.

- Dump all segments and sections using

otool:

otool -m /path_to_binary |

- Example:

Segment __PAGEZERO: 4294967296 (zero fill) |

The __PAGEZERO segment plays a crucial role in security. It sets up a memory area called the zero page at the very start of the address space for each process, but it makes this page completely unusable. The memory protection settings for this page are set to zero, meaning nothing can be read from, written to, or executed on this page. This design helps prevent security flaws, specifically NULL pointer dereference vulnerabilities, by ensuring that any attempt to access this low memory area will lead to an error, rather than allowing potentially harmful operations.

Explaining

| Segment | Size (Bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __PAGEZERO | 4294967296 | A zero-fill segment that protects against NULL pointer dereferences. |

| __TEXT | 32768 | Contains executable code and read-only data. |

| > __text | 15384 | The main body of executable code. |

| > __auth_stubs | 1344 | Stubs for authenticated pointers (part of code signing). |

| > __const | 212 | Read-only data constants. |

| > __cstring | 1268 | String literals, stored in a read-only section. |

| > __unwind_info | 212 | Information for stack unwinding during exceptions. |

| __DATA_CONST | 16384 | Read-only data that was originally in the __DATA segment. |

| > __auth_got | 672 | Authenticated pointers’ global offset table. |

| > __got | 48 | Non-authenticated global offset table for dynamic linking. |

| > __const | 616 | Constants that are now placed in a read-only section for security. |

| __DATA | 16384 | Contains mutable data accessed during execution. |

| > __data | 32 | Modifiable data used by the program. |

| > __common | 176 | Uninitialized data (zero-filled) used for global variables. |

| > __bss | 336 | Uninitialized data that does not occupy space in the file (zero-fill). |

| __LINKEDIT | 32768 | Contains raw data like symbol tables and string tables for dynamic linking. |

MacOS Binary Static Analysis

Codesign

| Command | Example Usage | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

codesign -d |

codesign -d /Applications/Automator.app |

Displays the code signature of the application. Useful for checking basic signature details without any modifications or verbose details. |

codesign -dv |

codesign -dv /System/Applications/Automator.app |

Displays the code signature with verbose information about the application. It provides more detailed insights into the signed application including platform identifiers and signature sizes. |

codesign -dvv |

codesign -dvv /System/Applications/Automator.app |

Increases the verbosity level further, showing even more detailed information like the authorities under which the app was signed. |

codesign -d --entitlements :- |

codesign -d --entitlements :- /System/Applications/Automator.app |

Displays the entitlements in a human-readable XML format. This is crucial for understanding what permissions the application has on a macOS system. |

Objdump

| Command | Example Usage | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

objdump -m |

objdump -m /path/to/binary |

Instructs objdump to parse the file as a Mach-O file. Use this when you need to analyze Mach-O formatted files specifically. |

objdump --dylibs-used |

objdump --dylibs-used /path/to/binary |

Lists the dynamic libraries (dylibs) that the binary depends on. Useful for understanding external dependencies of an executable or library. |

objdump -h |

objdump -h /path/to/binary |

Displays the headers of the sections of the Mach-O file. Use this to see detailed information about each section in the file, such as its size and address. |

objdump --syms |

objdump --syms /path/to/binary |

Displays the symbol table of the binary. This is useful for seeing all the symbols used in the file, including functions and variables, which can help with debugging and reverse engineering efforts. |

objdump --disassemble |

objdump --disassemble /path/to/binary |

Disassembles the executable sections of the binary. Use this command when you need to analyze the assembly code within the binary for a deeper understanding of its operation. |

objdump --full-contents |

objdump --full-contents /path/to/section |

Dumps the raw contents of specified sections. This is particularly useful when you need to inspect the actual data or code within a section of the binary. |

objdump --section-headers |

objdump --section-headers /path/to/binary |

Displays information about the header of each section in the binary. Useful for a quick overview of the section layout and characteristics. |

objdump --disassemble-functions=function_name --x86-asm-syntax=intel/att |

objdump --disassemble-functions=_main --x86-asm-syntax=intel/att /path/to/binary |

Disassembles a specific function within the binary. Useful when focusing on particular pieces of code for detailed analysis or debugging. |

Jtool2

| Command | Example Usage | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

jtool2 -l |

jtool2 -l /path/to/binary |

Lists all load commands and section details of a Mach-O file. Useful for getting a quick overview of the binary’s structure and contents. |

jtool2 -L |

jtool2 -L /path/to/binary |

Displays the dynamic libraries (dylibs) that the binary links against. Essential for understanding external dependencies. |

jtool2 -S |

jtool2 -S /path/to/binary |

Shows the symbol table of the binary, including both local and external symbols. Valuable for debugging and reverse engineering. |

jtool2 -v |

jtool2 -v /path/to/binary |

Provides verbose output for the given file, including detailed information on the binary’s headers, load commands, and more. |

ARCH=arch jtool2 --sig |

ARCH=x86_64 jtool2 --sig /path/to/binary |

Displays the code signature information, including certificate details, hashes, and more. Useful for security analysis. |

jtool2 --ent |

jtool2 --ent /path/to/binary |

Outputs the entitlements used by the binary in XML format. Crucial for assessing the permissions granted to the application. |

jtool2 -d |

jtool2 -d /path/to/binary |

Dumps disassembled code from the binary. Note that this is primarily intended for ARM binaries and might not fully support other formats. |

jtool2 --objc |

jtool2 --objc /path/to/binary |

Analyzes and outputs Objective-C runtime information, such as classes, methods, and protocols. |

jtool2 --analyze |

jtool2 --analyze /path/to/binary |

Performs an in-depth analysis of the binary, providing insights into potential vulnerabilities or unusual patterns in the code. |

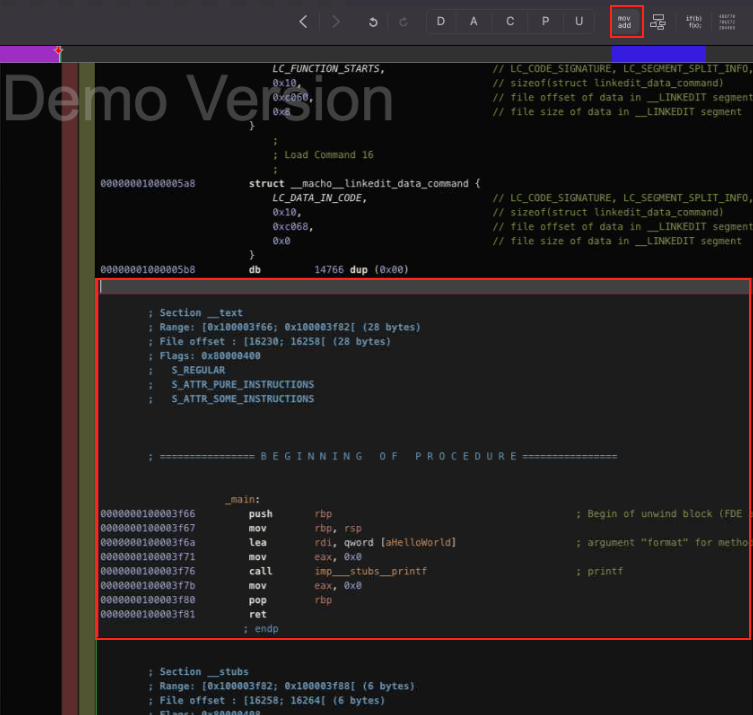

Hopper

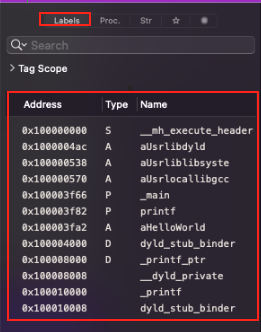

Lables

Address: This is the hexadecimal address of the label within the binary’s memory space. It points to where the label, which can be a function, a variable, or a marker, is located in the disassembled code.Type: Indicates the nature of the label. Common types include:S(Symbol) for named points in the code which could represent functions or markers placed by the compiler or the disassembler.A(Array) denoting the beginning of an array data structure.P(Procedure) representing the start of a procedure or function.D(Data) for locations that are marked to hold data rather than executable code.

Name: This is the name assigned to the label. It could be a name given by the programmer, or it could be a name generated by Hopper based on the label’s usage or content. For example:__mh_execute_headertypically marks the start of theMach-Oheader inmacOSexecutables._mainis the name conventionally given to the starting point of a C or C++ program.printfanddyld_stub_bindersuggest imported functions used for printing to the console and dynamic linking, respectively.

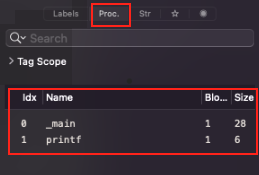

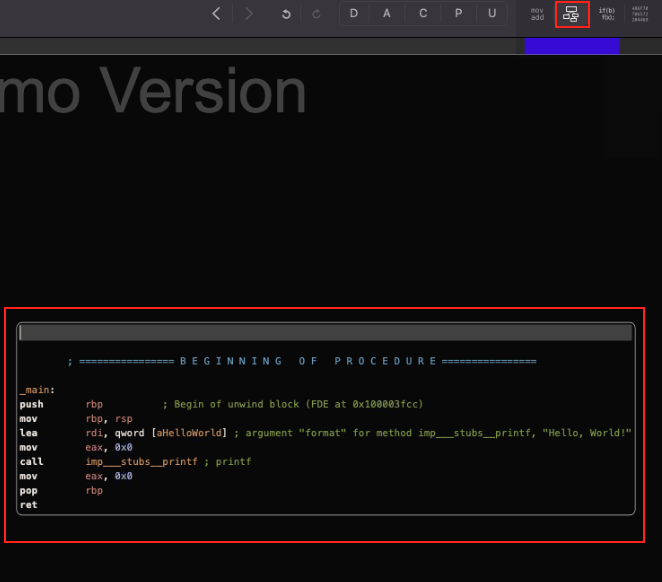

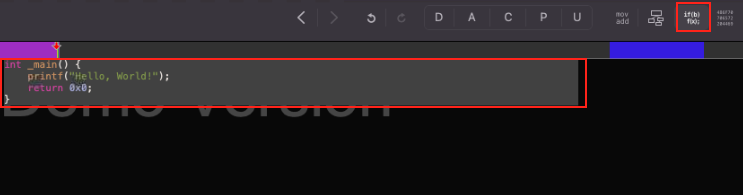

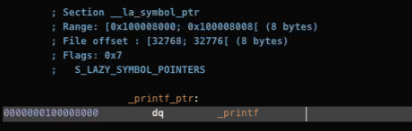

Functions

Idx(Index): This is a sequential number assigned to each procedure for easy reference. It typically starts from 0 and increments by 1 for each procedure discovered in the binary.Name: The name of the procedure, which can be the one assigned by the programmer or inferred from debugging symbols or imports within the binary. In this case, you have _main, which is typically the entry point for C programs, and printf, a standard C library function for printing formatted output to the console.Block: Indicates the basic block count within the procedure. A basic block is a straight-line code sequence with no branches in except to the entry and no branches out except at the exit. In the provided image, both _main and printf are part of one basic block.Size: Represents the size of the procedure in bytes. This tells you how much space the compiled machine code for this procedure occupies. _main is 28 bytes, while printf is 6 bytes.

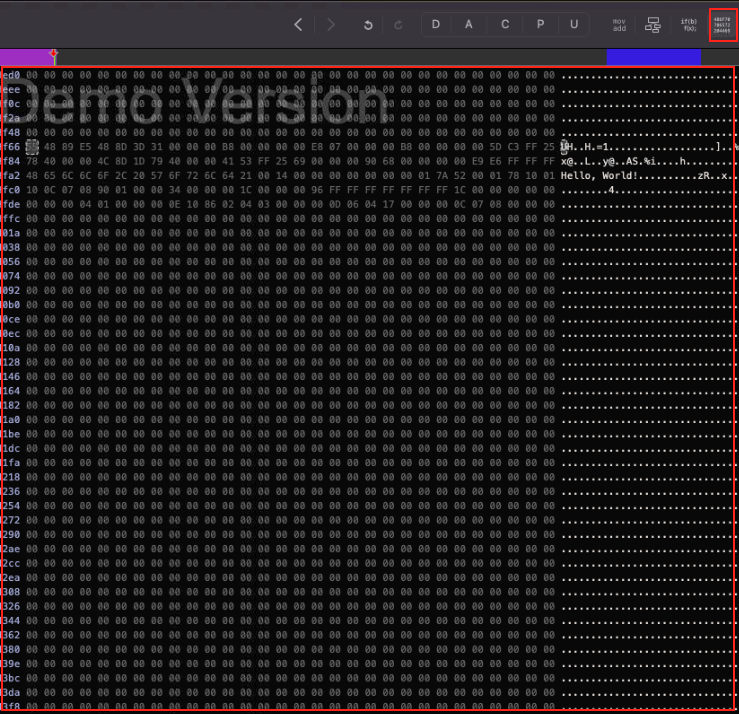

Strings

- Readabble Strings extracted from the binary

Disassembly view

Graphical View

Decompiling

Hex view

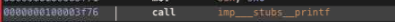

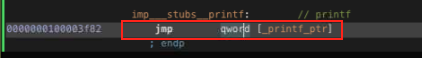

External functions Resolution

- External function

printf

- Double clicking on

imp___stubs__printftake us to the pointer:

- Double cliuck on

-printf_ptrtake us to the__la_symbol_ptrsection, which contains a list of external pointers.

And here where dynamic loader (dyld) will populate the address of the external function.

Useful table for static analysis with hopper

| Feature | Menu Path | Shortcut | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| New | File > New | Cmd + N | Creates a new file/workspace in Hopper. |

| Open | File > Open… | Cmd + O | Opens an existing file for disassembling. |

| Open Recent | File > Open Recent | Provides a submenu to open recently accessed files. | |

| Save | File > Save | Cmd + S | Saves the current state of the workspace. |

| Save As… | File > Save As… | Shift + Cmd + S | Saves the current workspace as a new file. |

| Import Types… | File > Import Types… | Imports type declarations from another file. | |

| Export Types… | File > Export Types… | Exports type declarations to a file. | |

| Import Types from C-like Header File… | File > Import Types from C-like Header File… | Imports types from a C-like header file to use in disassembly annotations. | |

| Export Objective-C Header File… | File > Export Objective-C Header File… | Exports an Objective-C header file based on the classes and methods detected in the binary. | |

| Produce Assembly Text File… | File > Produce Assembly Text File… | Generates an assembly listing of the entire binary or selected portion to a text file. | |

| Produce Assembly For Current Procedure… | File > Produce Assembly For Current Procedure… | Outputs the assembly code for the currently selected procedure to a text file. | |

| Produce Pseudo-Code File For Current Procedure… | File > Produce Pseudo-Code File For Current Procedure… | Generates pseudo-code for the current procedure and exports it to a file. | |

| Read Executable to Disassemble… | File > Read Executable to Disassemble… | Shift + Cmd + O | Opens a dialog to select an executable file specifically for disassembly. |

| Read File From DYLD Cache… | File > Read File From DYLD Cache… | Allows reading and disassembling of binaries directly from the DYLD shared cache. | |

| Copy | Edit > Copy | Cmd + C | Copies the selected content to the clipboard. |

| Copy Hex String of Selected Bytes | Edit > Copy Hex String of Selected Bytes | Cmd + Shift + C | Copies the selected bytes as a hexadecimal string to the clipboard. |

| Select All | Edit > Select All | Cmd + A | Selects all content in the current context or field. |

| Select Procedure | Edit > Select Procedure | Cmd + Shift + A | Selects the entire procedure (function) that the cursor is currently in. |

| Mark as Code | Modify > Code > Code | Cmd + P | Interprets the selected bytes as executable code. |

| Mark as Data Array | Modify > Data > Array | Cmd + Shift + D | Marks the selection as a data array, interpreting the bytes as a series of data elements. |

| Mark as NULL-Terminated C String | Modify > Data > NULL-Terminated C String | Cmd + Shift + A | Interprets the selected bytes as a NULL-terminated C string. |

| Mark as Unicode String | Modify > Data > Unicode String | Cmd + Shift + U | Marks the selection as a Unicode string, interpreting the bytes as characters in Unicode encoding. |

| Assemble Instruction… | Modify > Assemble Instruction… | Cmd + Shift + A | Opens a dialog allowing you to input and compile assembly instructions to replace existing code at the selection. |

| Go To Address or Symbol… | Navigate > Go To Address or Symbol… | G | Jumps to the inputted address or symbol within the binary. |

| Go To File Offset… | Navigate > Go To File Offset… | Shift + G | Moves to the specified file offset, allowing for precise navigation based on file structure. |

| Show Segment List… | Navigate > Show Segment List… | Cmd + S | Displays a list of all segments in the binary. |

| Show Section List… | Navigate > Show Section List… | Shift + Cmd + S | Displays a list of all sections in the binary. |

| Next Code | Navigate > Next Code | Cmd + C | Jumps to the next chunk of code in the binary. |

| Next Data | Navigate > Next Data | Cmd + D | Jumps to the next data section in the binary. |

| Next Procedure | Navigate > Next Procedure | Cmd + P | Moves to the next defined procedure or function. |

| References To Highlighted Word… | Navigate > References To Highlighted Word… | Cmd + R | Lists all the references to the currently highlighted word in the code. |

| Search for Symbol… | Navigate > Search for Symbol… | Cmd + F | Opens a search dialog to quickly find symbols within the binary. |

| Show Control Flow Graph | Window > Show Control Flow Graph | Space | Displays the control flow graph for the current procedure. |

| Show Pseudo Code of Procedure | Window > Show Pseudo Code of Procedure | Cmd + Option + P | Opens the pseudo code representation of the current procedure. |

| Show Hexadecimal Editor | Window > Show Hexadecimal Editor | Cmd + Option + H | Opens the hexadecimal view of the binary. |

MacOS Binary Dynamic Analysis

Debugging Rules

The rules for debugging applications on macOS;

Debugging Signed Applications with Entitlements:

- Applications that are signed and have the

com.apple.security.get-task-allowentitlement can be debugged by a standard user. This entitlement specifically allows other processes, like debuggers, to attach to the application. Xcode automatically adds this entitlement to apps when they are built for development.

- Applications that are signed and have the

Applications Protected by SIP:

- System Integrity Protection (SIP) restricts debugging of system binaries or those signed with hardened runtime unless the target application has the

com.apple.security.get-task-allowentitlement. To debug such applications, the debugger itself must have thecom.apple.security.cs.debuggerentitlement.

- System Integrity Protection (SIP) restricts debugging of system binaries or those signed with hardened runtime unless the target application has the

Debugging Non-Protected Applications:

- Applications not protected by SIP and without the

com.apple.security.get-task-allowentitlement can still be debugged if the user runs the debugger as root or authenticates as an admin.

- Applications not protected by SIP and without the

Limitations on Debugging System Binaries or Hardened Runtime Applications:

- You cannot debug system binaries or applications signed with hardened runtime as part of Apple’s notarization requirements, unless they have the

com.apple.security.get-task-allowentitlement.

- You cannot debug system binaries or applications signed with hardened runtime as part of Apple’s notarization requirements, unless they have the

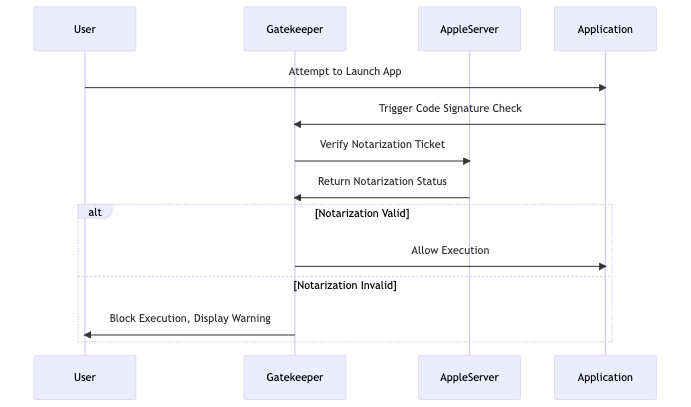

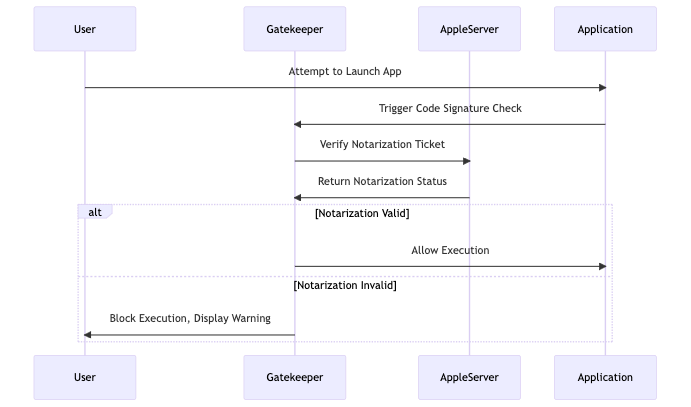

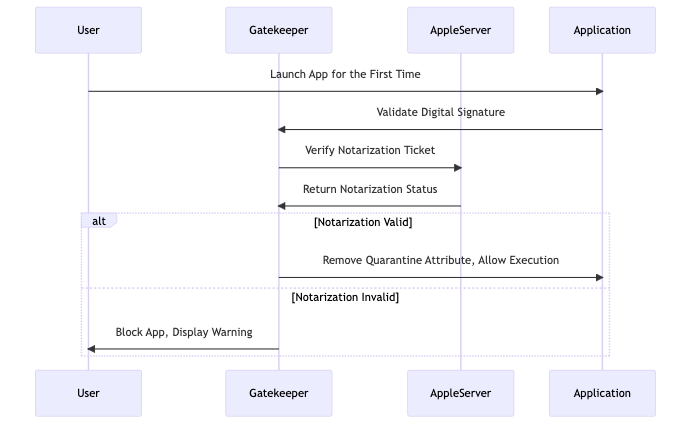

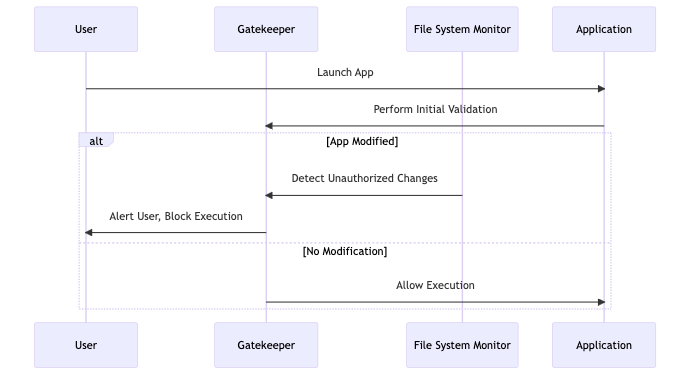

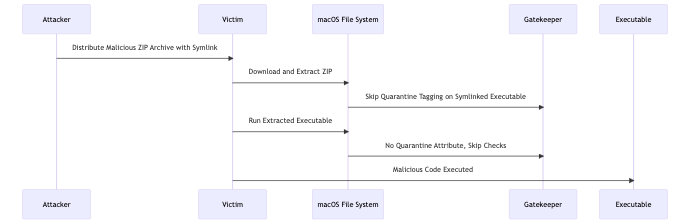

Notarization:

- Notarization is an Apple security process for scanning applications for malicious content before distribution. If an app is not notarized, Gatekeeper may block its execution to protect the system.

Disabling SIP:

- While disabling SIP would technically allow debugging of any application, it is not recommended. SIP provides critical protections beyond just debugging restrictions, including protecting core system files and preventing unsigned kernel extensions from loading. Disabling SIP significantly weakens macOS security.

LLDB

Esssentail Start

| Category | Name | Command | Shortcut | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential Start | ||||

| Open Executable | target create |

(lldb) target create "./executable" |

Loads a new executable for debugging. | |

| Attach Process | process attach |

(lldb) process attach --pid <PID> |

Attaches the debugger to an existing process by PID. | |

| Stop Debugging | process kill |

(lldb) process kill |

Terminates the current debugging session. | |

| Go | process continue |

(lldb) process continue |

c |

Continues execution after a breakpoint or pause. |

| Restart | process launch |

(lldb) process launch --stop-at-entry |

Restarts the current debugging session and stops at the entry point. | |

| Step Into | thread step-in |

(lldb) thread step-in |

si |

Executes one line or instruction at a time, stepping into functions. |

| Step Over | thread step-over |

(lldb) thread step-over |

ni |

Executes the next line or instruction, stepping over function calls. |

| Step Out | thread step-out |

(lldb) thread step-out |

finish |

Continues execution until the current function completes. |

| Monitoring & Debugging Windows | ||||

| Command Interface | LLDB console |

Access through terminal or IDE console | The primary interface for all LLDB commands. | |

| Watchpoint Set | watchpoint set |

(lldb) watchpoint set variable myVar |

Sets a watchpoint for a variable to monitor its value changes. | |

| View Local Variables | frame variable |

(lldb) frame variable |

Displays local variables in the current frame. | |

| View Registers | register read |

(lldb) register read |

Displays the values of CPU registers. | |

| View Memory | memory read |

(lldb) memory read <ADDRESS> |

Allows examination of memory contents. | |

| View Call Stack | bt |

(lldb) bt |

Displays the current call stack. | |

| View Disassembly | disassemble |

(lldb) disassemble --name main |

Shows disassembled code for a function. | |

| Advanced Usage & Customization | ||||

| Python Scripting | command script |

(lldb) command script add -f my_script.my_func my_cmd |

Adds a custom command using a Python function. | |

| Aliases & Shortcuts | command alias |

(lldb) command alias b breakpoint set |

Creates custom aliases for existing commands. | |

| LLDB Init File | ~/.lldbinit |

Include commands in ~/.lldbinit |

Loads custom LLDB settings and commands on startup. | |

| Extend LLDB | Custom Python scripts | Use script command to run Python |

Write and run Python scripts for complex debugging tasks. |

Symbols

| Category | Command/Action | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol Configuration | |||

| Set Symbol File Path | target symbols add |

Adds a new symbol file to the current target. | (lldb) target symbols add /path/to/symbols |

| Append Symbol Search Path | settings set target.exec-search-paths |

Appends new paths to the symbol search paths. | (lldb) settings set target.exec-search-paths /path/to/symbols |

| Reload Symbols | target modules reload |

Reloads symbol information for a specific module. | (lldb) target modules reload --filename libmylib.dylib |

| List Symbol Search Paths | settings show target.exec-search-paths |

Displays the current symbol search paths. | (lldb) settings show target.exec-search-paths |

| Clear All Symbol Information | target symbols clear |

Clears all symbol information from the current target. | (lldb) target symbols clear |

Display & Manupilating ( CPU & Memory):

| Category | Command/Action | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Examination | |||

| Disassemble Memory | disassemble --start-address |

Disassembles code starting from a specified address. | (lldb) disassemble --start-address 0x00400000 |

| Read Memory | memory read |

Displays memory content at a specified address. | (lldb) memory read 0x00400000 |

| Write Memory | memory write |

Writes data to a specified memory address. | (lldb) memory write 0x00400000 0x90 |

| Memory Dumping | |||

| Dump Memory as Bytes | memory read --format b |

Reads memory content as bytes. | (lldb) memory read --format b 0x00400000 |

| Dump Memory as Words | memory read --format w |

Reads memory content as 16-bit words. | (lldb) memory read --format w 0x00400000 |

| Dump Memory as Double Words | memory read --format W |

Reads memory content as 32-bit double words. | (lldb) memory read --format W 0x00400000 |

| Dump Memory as Quad Words | memory read --format q |

Reads memory content as 64-bit quad words. | (lldb) memory read --format q 0x00400000 |

| Dump Memory as Pointers | memory read --format p |

Reads memory content as pointer values. | (lldb) memory read --format p 0x00400000 |

| Searching in Memory | |||

| Search for Byte Pattern | memory find |

Searches memory for a specific byte pattern. | (lldb) memory find 0x00400000 0x00401000 0x90 |

| Search for ASCII String | memory find --string |

Searches memory for an ASCII string. | (lldb) memory find --string 0x00400000 0x00401000 "Hello" |

| CPU Registers Manipulation | |||

| Show All Registers | register read |

Displays all CPU registers. | (lldb) register read |

| Read Specific Register | register read |

Displays a specific register value. | (lldb) register read eax |

| Write to Register | register write |

Writes a value to a specific register. | (lldb) register write eax 5 |

| Memory Formatting Options | |||

| Read Memory as ASCII String | memory read --format s |

Reads memory content as ASCII strings. | (lldb) memory read --format s 0x00400000 |

| Read Memory as Unicode String | memory read --format U |

Reads memory content as Unicode strings. | (lldb) memory read --format U 0x00400000 |

| Write ASCII String to Memory | memory write --format s |

Writes an ASCII string to memory. | (lldb) memory write --format s 0x00400000 "Hello, World!" |

| Write Unicode String to Memory | memory write --format U |

Writes a Unicode string to memory. | (lldb) memory write --format U 0x00400000 "Hello, World!" |

| Read Memory as Hex String | memory read --format x |

Reads memory content and displays it as hex. | (lldb) memory read --format x 0x00400000 |

| Read Memory as Decimal | memory read --format d |

Reads memory content and displays it as decimal. | (lldb) memory read --format d 0x00400000 |

Breakpoints in LLDB

| Breakpoint Type | Command Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Software Breakpoints | breakpoint set --address [Address] |

Sets a software breakpoint at a specified memory address. |

breakpoint set --name [Function] --shlib [Module] |

Sets a breakpoint at the start of a function within a specific module. | |

| Unresolved Breakpoints | breakpoint set --name [Function] |

Sets a breakpoint that will resolve when the function is loaded into memory. |

| Conditional Breakpoints | breakpoint set --name [Function] --condition '[Condition]' |

Sets a breakpoint with a condition. The breakpoint will only trigger if the condition evaluates to true. |

breakpoint command add [BreakpointID] --python '[PythonScript]' |

Attaches a Python script to a breakpoint. The script executes when the breakpoint hits. | |

| Breakpoint-Based Actions | breakpoint command add [BreakpointID] |

Attaches a series of LLDB commands to a breakpoint, which are executed when the breakpoint is hit. |

| Hardware Breakpoints | breakpoint set --hardware --address [Address] |

Sets a hardware breakpoint at a specified address. |

Debugging (Stepping & Tracing) in LLDB

| Action | Command | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step Over | thread step-over |

(lldb) thread step-over |

Executes the next line or instruction, stepping over function calls. |

| Step Into | thread step-in |

(lldb) thread step-in |

Executes the next line or instruction, stepping into functions and calls. |

| Step Over with Count | thread step-over --count [n] |

(lldb) thread step-over --count 2 |

Executes the next [n] instructions, stepping over any function calls. |

| Step Into with Count | thread step-in --count [n] |

(lldb) thread step-in --count 2 |

Executes the next [n] instructions, tracing into any function calls. |

| Step Out | thread step-out |

(lldb) thread step-out |

Continues execution until the current function returns to its caller. |

| Step to Next Return | thread until-return |

(lldb) thread until-return |

Executes until the current function returns. |

| Step to Next Branch | thread until-branch |

(lldb) thread until-branch |

Executes until it reaches any branching instruction. |

| Step to Next Call | thread until-call |

(lldb) thread until-call |

Executes until a call instruction is reached within the current function. |

| Step Until Address | thread until --address [addr] |

(lldb) thread until --address 0x00400000 |

Continues execution until reaching the specified address. |

Modules & Info Commands in LLDB

| Command | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| List Loaded Modules | image list |

Lists all modules loaded by the process along with detailed information. |

image list [pattern] |

(lldb) image list libc |

Lists modules that match the given pattern, useful for filtering specific libraries or modules. |

| Examine Symbols | image lookup --name [name] |

Looks up symbols by name across all modules. |

image lookup --name [name] --shlib [module] |

(lldb) image lookup --name strcpy --shlib libc |

Lists symbols within a specific module that match the symbol name provided. |

| Address Information | image lookup --address [addr] |

Provides detailed information about the function or symbol at the specified address including the module it belongs to. |

| Memory Protection Attributes | Not directly supported in LLDB | LLDB does not directly provide page protection details, typically handled by OS-specific commands or tools. |

| Thread Environment Block | Access via memory read | (lldb) memory read --format x --size 8 --count 1 $teb |

| Process Environment Block | Access via memory read | (lldb) memory read --format x --size 8 --count 1 $peb |

Evaluate Expression in LLDB

| Command | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluate Expression | expression |

Evaluates C/C++ expressions, including function calls and accessing variables. |

| expression [expr] | (lldb) expression 3 + 4 |

Evaluates the sum of 3 and 4. |

| Convert Hex to Dec | expression (int)0x20 |

Converts a hexadecimal number to its decimal equivalent. |

| Convert Dec to Hex | expression (hex)54 |

Converts a decimal number to its hexadecimal equivalent. Note: Use format specifiers for output formatting. |

| Bitwise Shift | expression 3 << 1 |

Performs a bitwise left shift on a number, effectively multiplying it by 2. |

| Bitwise AND | expression 0x12345678 & 0xffff |

Performs a bitwise AND operation to mask certain bits. |

| Use Register Value | expression $rip + 24 |

Evaluates an expression using the current value of the rip register (note: rip for x64, eip for x86) and adds a value to it. |

| Negative Hex Representation | expression -0x0fe |

Evaluates the negative hexadecimal representation of a number. |

| Evaluate with Context | expression -- [expr] |

Evaluates expressions with full access to the program’s variables and memory. |

(lldb) expression -- (char*)$rdi |

Interprets the value of the rdi register as a pointer to a character (string). | |

| Format Results in Hex | expression -f x -- (expression) |

Formats the result of an expression in hexadecimal. |

LLDB Scripting

| Description | Script Command | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assign a value to a pseudo-register | command script add |

(lldb) command script add -f my_script.set_register my_cmd |

Adds a custom command that sets a register value, defined in a Python function my_script.set_register. |

| Execute a command repeatedly | Python looping in script | (lldb) command script add -f my_script.loop_command my_loop |

Adds a loop command defined in my_script.loop_command to execute LLDB commands repeatedly. |

| Conditional breakpoint with script | breakpoint command add |

(lldb) breakpoint set --name func -c "int_var == 1" |

Sets a conditional breakpoint that only triggers if int_var equals 1. |

| Write to a log file | Python scripting to log output | (lldb) command script add -f my_script.log_output log_cmd |

Custom script to log debugging output to a file, defined in my_script.log_output. |

| Branching in script | Python if-else in command script | (lldb) command script add -f my_script.check_condition check_cmd |

Implements branching logic within an LLDB command script defined in my_script.check_condition. |

| Using aliases | command alias |

(lldb) command alias ls_regs register read |

Creates an alias ls_regs for the register read command. |

| Script loops with aliases | Python loops to execute commands | Define a loop in a Python script and use lldb API to execute LLDB commands within the loop. |

Useful for repetitive tasks, where Python controls the loop logic. |

| Data manipulation with scripts | Use Python scripts for data manipulation | (lldb) command script add -f my_script.manipulate_data data_cmd |

Custom script to manipulate data, defined in my_script.manipulate_data. |

| Logging with a condition | Conditional logging via Python script | (lldb) command script add -f my_script.conditional_log log_if_cmd |

Adds conditional logging functionality through a custom script my_script.conditional_log. |

| Iterating over a list of addresses | Python for loop in scripting | Script a Python for loop to iterate over addresses and execute LLDB commands. | Use Python to automate tasks over a range of memory addresses. |

| Conditionally modifying memory | Use Python conditionals and LLDB commands | Define conditions in Python and use LLDB API to modify memory based on these conditions. | Combines Python’s conditional logic with memory modification commands in LLDB. |

| Running a script file | command source |

(lldb) command source /path/to/my_script.lldb |

Executes LLDB commands from a script file. |

| Custom command sequences | command script add |

(lldb) command script add -f my_script.custom_sequence my_sequence |

Adds a custom command sequence defined in my_script.custom_sequence. |

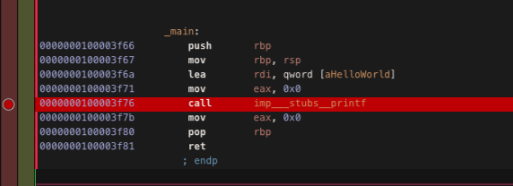

Hopper

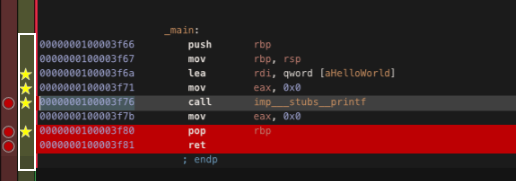

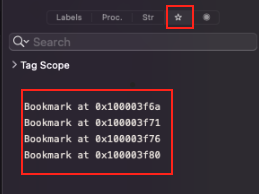

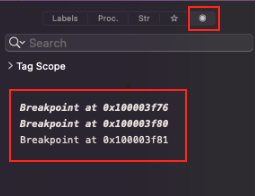

Set a breakpoint

- One the red line on the left side click on the line you want to set breakpoint at:

BookMark an instruction

- On the green line on the left side click on the line next to the instruction you want to bookmark:

Bookark list

Breakpoints list

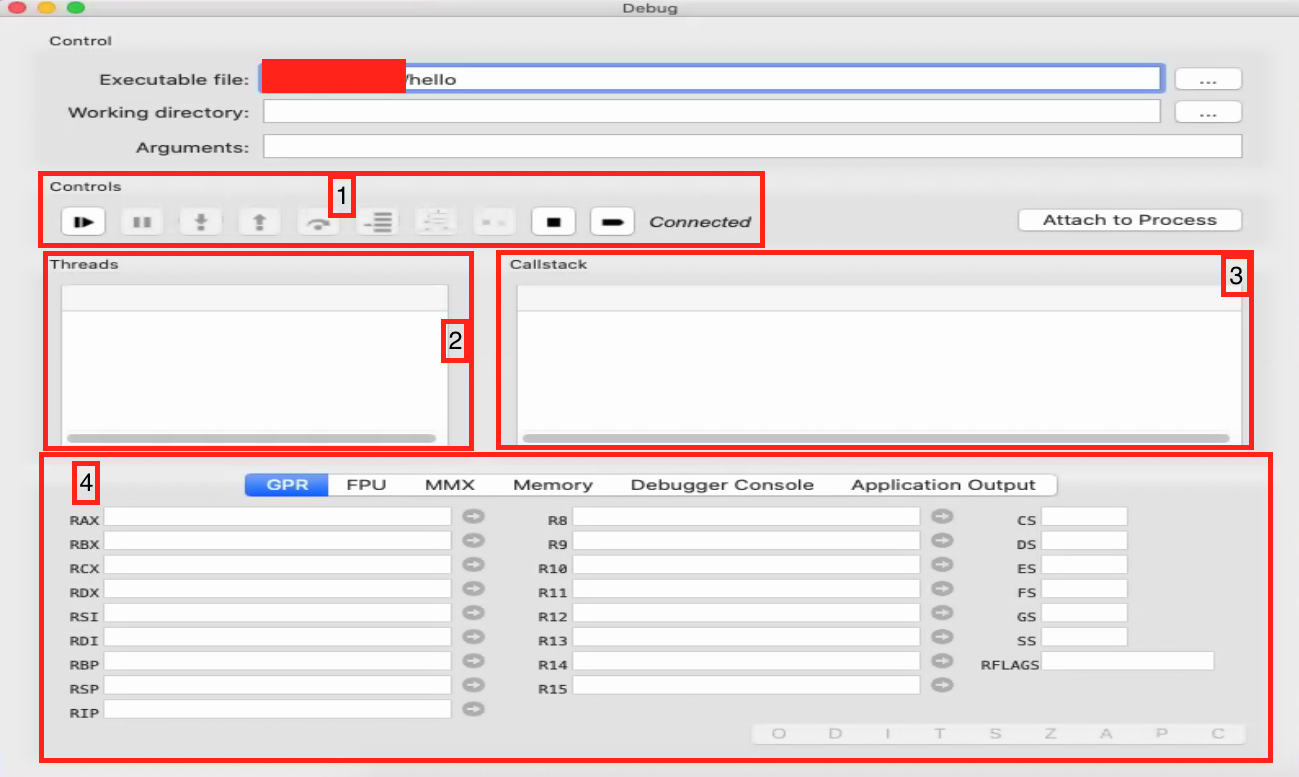

Debugger

- Choose the local or remote debugging

Local Debugging

Controls:

- This area typically contains buttons for controlling the debugging session, such as starting/pausing the execution (Play/Pause buttons), stopping the debug session, stepping into/over/out of functions (Step commands), and potentially restarting the debugged program. The “Connected” indicator suggests a successful attachment to the process or target for debugging.

Threads and Callstack:

- This section is split into two main parts:

- Threads: Shows a list of all the threads in the current debugging session. You can select a thread to view its call stack and register state.

- Callstack: Displays the call stack of the selected thread. The call stack lists the sequence of function calls that are currently active. It starts with the current function where the execution is paused and goes back to the initial function call.

- This section is split into two main parts:

Attach to Process:

- This button is used to attach the debugger to a running process. You can use this if you want to debug a program that is already running rather than starting a new debug session.

Register Groups:

- The register tabs (GPR, FPU, MMX, etc.) organize the display of the CPU’s registers into groups:

- GPR (General Purpose Registers): Displays general-purpose registers like RAX, RBX, RCX, etc. These registers are used for a variety of purposes, including arithmetic and data manipulation.

- FPU (Floating-Point Unit Registers): Shows the state of floating-point registers used for floating-point arithmetic operations.

- MMX (Multimedia Extensions Registers): Lists MMX registers which are used for multimedia tasks like audio or video processing.

- Each register may have indicators or buttons next to them for additional functionalities like setting watchpoints or modifying their values.

- Memory: A tab or section for viewing and editing the memory of the process being debugged.

- Debugger Console: An interface for typing commands directly into the debugger, similar to a command-line interface.

- Application Output: Where the standard output and error streams from the debugged process are displayed. This is where you would see print statements or error messages from the program.

- Various CPU registers state (right side): Displaying the current state of additional registers, like segment registers (CS, DS, ES, etc.) and flags (RFLAGS), providing status flags and control bits used by the CPU.

- The register tabs (GPR, FPU, MMX, etc.) organize the display of the CPU’s registers into groups:

DTrace

DTrace is a comprehensive dynamic tracing framework that is integrated into the XNU kernel on macOS. It provides detailed real-time insights into kernel and application behavior.

DTrace Basic Terms

- Providers: Modules within the kernel that offer tracing functionality. Example:

syscall. - Probes: Trace points within providers that monitor specific events, like function entry and exit.

- DTrace Consumers: Utilities that interact with DTrace, such as the

dtracecommand. - D Language: Scripting language used to write DTrace programs.

DTrace and Utilities for Different Usages

| Utility/Command | Options | Usage | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

dtrace |

-l |

List Probes | Lists all DTrace probes available on the system. |

dtrace |

-n 'probe description' |

Start Tracing | Initiates tracing based on a specified probe description. |

dtrace |

-s script.d |

Run Script | Executes a DTrace script from a file. |

dtrace |

-q |

Quiet Mode | Suppresses output of DTrace actions, useful for scripts that do not require immediate console output. |

dtruss |

-n process |

Trace Process | Runs the dtruss script to trace system calls made by the specified process. |

dtruss |

-e |

Trace Executable | Traces system calls when a specific executable is run. |

dtruss |

-p PID |

Trace PID | Attaches to an existing process and traces its system calls. |

iosnoop |

N/A | I/O Monitor | Monitors file I/O activity in real-time. |

opensnoop |

-n process |

File Access Monitor | Monitors files being opened by a specific process. |

execsnoop |

N/A | Exec Calls Monitor | Monitors execution of processes. |

errinfo |

N/A | Error Monitor | Monitors system call failures. |

dapptrace |

-p PID |

Application Tracer | Traces application-level activity for the specified process ID. |

bitesize.d |

N/A | Disk I/O Size Analysis | Analyzes disk I/O size by process, using DTrace. |

Examples of DTrace Script Usage

List all syscall probes for open calls

sudo dtrace -l -n 'syscall::open*:entry'

Trace system calls for a process named ‘myapp’

sudo dtrace -n 'syscall:::entry /execname == "myapp"/ { trace(probefunc); }'

Run a DTrace script from a file

sudo dtrace -s /path/to/myscript.d

Trace file opens for process ID 12345 using opensnoop

sudo opensnoop -p 12345

Monitor disk I/O size by process using bitesize.d

sudo bitesize.d

- Scripting with

dtrace:

Shellcoding On AMD64

macOS System Call Classes

| Class Number | Class Name | Description | Masked Value Example |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_NONE |

Invalid System Calls | 0x0000000 |

1 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_MACH |

Mach-related System Calls | 0x01000000 |

2 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_UNIX |

Unix/BSD System Calls | 0x02000000 |

3 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_MDEP |

Machine-dependent Syscalls | 0x03000000 |

4 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_DIAG |

Diagnostic System Calls | 0x04000000 |

5 |

SYSCALL_CLASS_IPC |

Mach IPC System Calls | 0x05000000 |

Each system call class is associated with a unique number, which is shifted left by 24 bits (defined by SYSCALL_CLASS_SHIFT) to determine its class. The SYSCALL_CLASS_MASK and SYSCALL_NUMBER_MASK are used to extract the class and syscall number respectively.

For example, a traditional BSD system call such as execve (system call number 59 or 0x3b) in the SYSCALL_CLASS_UNIX (number 2) would be represented as 0x200003b when passed to the syscall assembly instruction.

; Assembly example to make a syscall with execve (BSD) in macOS |

Calling Conventions and Registers for Shellcoding on macOS (AMD64)

| Register | Usage |

|---|---|

RDI |

1st function argument |

RSI |

2nd function argument |

RDX |

3rd function argument (and optionally the 2nd return value) |

RCX |

4th function argument |

R8 |

5th function argument |

R9 |

6th function argument |

RAX |

Function return value |

RIP |

Instruction pointer |

RSP |

Stack pointer (must be 16-byte aligned before calls) |

RBP |

Frame pointer |

RBX |

Base pointer (optional use) |

If a function requires more than six arguments, additional arguments are passed on the stack. It is essential to ensure that the RSP is properly aligned before making a function call. Despite system calls often working without strict alignment, adhering to this requirement is a good practice to avoid unexpected behavior.

Example

To illustrate how these registers are used in a function call, consider a function foo that takes three arguments.

; Assume arg1, arg2, and arg3 are already set with appropriate values |

Syscalls

You can find system calls numbers in the syscalls.master under the xnu source, You could choose the one you need with the version from the following link:

Avoid Null-Bytes in Syscalls

To find out the bit number to set with the bts instruction, you need to compare the binary representation of the syscall number (example: 0x3b) with the binary representation of the syscall number plus the class mask (0x200003b). The echo and bc commands can be used to convert hexadecimal numbers to binary, and the xargs, printf, and tr commands format the output to compare the bits easily.

- Convert the syscall number (0x3b) to binary:

echo "obase=2; ibase=16; 3B" | bc | xargs printf "%064s\n" | tr ' ' '0' |

This command will output the binary representation of 0x3b as a 64-bit number, padded with zeroes.

- Convert the syscall number with the class mask (0x200003b) to binary:

echo "obase=2; ibase=16; 200003B" | bc | xargs printf "%064s\n" | tr ' ' '0' |

This command will output the binary representation of 0x200003b as a 64-bit number, padded with zeroes.

- Compare the Outputs:

Look for the first bit that differs when comparing the binary output from step 1 to the output from step 2. The differing bit’s position (starting from 0 on the right) is the bit you need to set with the bts instruction to transform the syscall number into the one with the class mask applied.

For instance, if the binary output for 0x3b is:

000...0000111011 |

And the binary output for 0x200003b is:

...0010000000000000000000111011 |

The differing bit is the 25th bit from the right (or the 24th index if you start counting from 0), which corresponds to the class mask.

Now, knowing that you need to set the 25th bit, you use the bts instruction with index 24 to set this bit in the register, as shown in the assembly example previously provided.

Syscall Number (0x3b): 000...0000111011 |

- Now executring the syscall:

push 59 ; put 59 on the stack |

Shellcoding on ARM64

Calling Conventions and Registers on macOS (Apple Silicon)

| Register | Usage | Description |

|---|---|---|

X0-X7 |

Function arguments and return values | Used to pass and return data from functions |

X8 |

Indirect return value address | Often used for memory allocation routines |

X9-X15 |

Caller-saved temporary registers | Can be changed by the called function, must be saved by the caller if needed |

X16 |

Inter-procedural scratch register; syscall number | Used for passing system call numbers |

X17 |

Inter-procedural scratch register | Temporary register, similar to X16 |

X18 |

Reserved on Apple platforms | Should not be used in user programs |

X19-X28 |

Callee-saved registers | Must be saved and restored by the called function if used |

X29 |

Frame pointer (FP) | Points to the base of the current stack frame |

X30 |

Link register (LR) | Stores the return address |

SP |

Stack pointer | Must be 16-byte aligned at function calls |

PC |

Program counter | Points to the next instruction to execute |

XZR |

Zero register | Always reads as zero and ignores writes |

The ARM64 architecture requires that the stack pointer (SP) is 16-byte aligned before making a function call, which is crucial for maintaining a reliable call stack and preventing alignment faults. When writing shellcode or functions in assembly, you need to preserve this alignment by adjusting the stack accordingly before function calls.

; Example assembly code for ARM64 macOS system call |

Syscalls

You can find system calls numbers in the syscalls.master under the xnu source, You could choose the one you need with the version from the following link:

Avoid Null-Bytes in Syscalls

Instead of performing the syscall using svc 0, the argument for for svc is aribtrary value, So it can be replaced:

mov x16, #SYS_write ; Load the syscall number for 'write' into X16 |

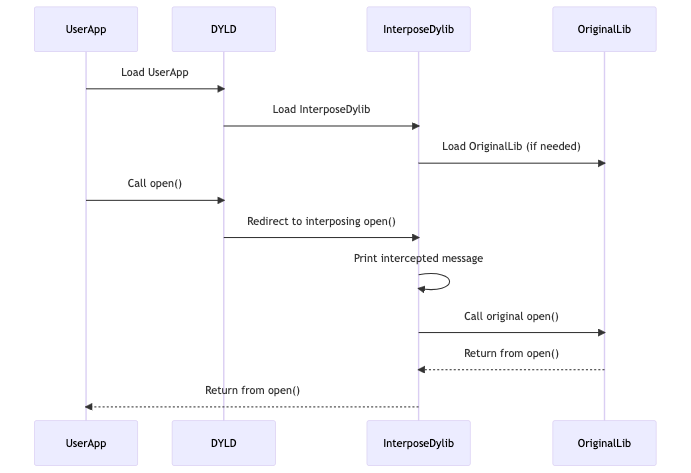

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES Injection

Understanding DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES:

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIESis an environment variable similar toLD_PRELOADon Linux.- It specifies a list of dynamic libraries to load before the application’s own libraries.

- Libraries specified in

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIESare loaded and executed in the context of the target application.

Creating a Dynamic Library:

Write a C file for the dynamic library that will be injected. Example code:

__attribute__((constructor))

static void myconstructor(int argc, const char **argv) {

printf("[+] dylib constructor called from %s\n", argv[0]);

syslog(LOG_ERR, "[+] dylib constructor called from %s\n", argv[0]);

}Compile this code into a dynamic library using GCC:

gcc -dynamiclib example.c -o example.dylib

Preparing the Target Application:

Create a simple application to test the injection, such as a “Hello World” program:

int main() {

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}Compile the application:

gcc hello.c -o hello

Performing the Injection:

Set the

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIESenvironment variable to point to the compiled dylib and run the target application:DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=example.dylib ./hello

The output should confirm that the dylib was loaded before the application’s main function:

[+] dylib constructor called from ./hello

Hello, World!

Monitoring Logs:

Use macOS’s logging system to confirm the injection and monitor behaviors:

log stream --style syslog --predicate 'eventMessage CONTAINS[c] "constructor"'

This command filters and streams log messages containing “constructor”, showing live outputs as the injected dylib executes.

Restrictions of DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES

To mitigate the abuse of the DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES environment variable, Apple has implemented specific restrictions in the dyld loader. The key function in the dyld source code that manages the restrictions is pruneEnvironmentVariables, which is responsible for removing certain environment variables during the load process:

static void pruneEnvironmentVariables(const char* envp[], const char*** applep) { |

The removal of variables is influenced by:

Setuid/setgid Executables:

- Environment variables starting with

DYLD_are ignored if the executable has setuid or setgid bits set. This is a security measure to prevent privilege escalation by injecting unauthorized code into a higher-privileged process.

- Environment variables starting with

Executables with Restricted Segment:

- If the executable contains a

__RESTRICT/__restrictsegment in the Mach-O file,DYLD_environment variables are also ignored. This segment signals that the binary opts out of certain dynamic loading features to increase its security stance.

- If the executable contains a

Entitlements and Code Signing:

- Executables that are code signed with entitlements may have restrictions on environment variables. If the

CS_RESTRICTflag is set in the code signature, it indicates that the process is restricted, leading to the ignoring ofDYLD_variables.

- Executables that are code signed with entitlements may have restrictions on environment variables. If the

Understanding processRestricted Function

The processRestricted function is pivotal in setting up the reasons for restrictions:

static bool processRestricted(const macho_header* mainExecutableMH) { |

- This function checks for

setuid/setgidstatuses and whether the executable’s code signature defines it as restricted.

Debugging AMFI

- Setup:

- Use

lldbto attach to the process or during the process launch. - Set a breakpoint on

amfi_check_dyld_policy_selfto inspect howAppleMobileFileIntegrity(AMFI) influences the loading of dynamic libraries.

- Use

(lldb) b amfi_check_dyld_policy_self |

Debugging:

- Continue execution to reach the breakpoint, then step through the code to observe how input flags are processed and output flags are set.

Inspecting AMFI Output Flags:

- After the syscall, The output flags from

amfi_check_dyld_policy_self(stored inRCXregister) determine what an application can do concerning dynamic library loading. Each flag corresponds to a specific permission:- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_AT_PATH: Allows loading dylibs from arbitrary paths.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_PRINT_VARS: Permits printing environment variables.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_PATH_VARS: Allows using path variables.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_CUSTOM_SHARED_CACHE: Permits custom shared cache settings.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_FALLBACK_PATHS: Enables fallback paths for library loading.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_FAILED_LIBRARY_INSERTION: Allows the insertion of libraries even if they fail some checks.

- AMFI_DYLD_OUTPUT_ALLOW_LIBRARY_INTERPOSING: Permits library interposing.

- After the syscall, The output flags from

SIP and AMFI Bits

System Integrity Protection (SIP) Bits:

- SIP is controlled using specific configuration flags. Each bit in the configuration represents a different aspect of system protection, such as allowing debugging or kernel extensions. These are set in the csrActiveConfig and checked against desired permissions.

- Example flag:

CSR_ALLOW_TASK_FOR_PIDallows debugging processes.

AMFI Policy Output Flags:

- These flags are set based on the security policy checks performed by AMFI. They influence the loader’s behavior regarding environment variables and dynamic loading.

- To interpret the flags, convert the output integer to binary and match each bit to the flag definitions.

Checking Flags

- Use shell commands to interpret numeric values into binary for easier flag analysis:

echo "obase=2; ibase=16; $(printf '%X' $FLAGS)" | bc |

Script to check AMFI flags

|

- Compile and run:

Compile |

Script to check SIP(CSR) flags

|

- Compile and run:

Compile |

Verifying Restrictions of DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES

Setting Up and Testing SUID Restrictions

- Change ownership and set SUID bit:

- Change the ownership of the binary to root and set the SUID bit to enable execution with root privileges.

sudo chown root hello |

Testing dylib injection with SUID bit set:

- When attempting to inject a dylib into a binary with the SUID bit set, the injection should fail, indicating the security measures are working as expected.

./hello # Normal execution |

Remove SUID bit and test dylib injection:

- Removing the SUID bit and attempting dylib injection again should succeed, demonstrating that the restriction is specifically linked to the SUID bit.

sudo chmod -s hello |

Testing Restricted Segments

Add a restricted segment to the binary:

- Compiling a binary with a specific segment (

__RESTRICT/__restrict) that signals dyld to ignore certain dynamic loading features.

- Compiling a binary with a specific segment (

gcc -sectcreate __RESTRICT __restrict /dev/null hello.c -o hello-restricted |

Attempt dylib injection into the restricted binary:

- Injection attempts should fail, confirming that the restricted segment is recognized and respected by dyld.

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=example.dylib ./hello-restricted |

Verify the presence of the restricted segment:

- Using the

sizecommand to verify the segments and sections of the compiled binary, confirming the presence of the__RESTRICTsegment.

- Using the

size -x -l -m hello-restricted |

Hardened Runtime and Code Signing

Enable hardened runtime and code-sign the binary:

- Applying a hardened runtime setting to the binary using a self-signed certificate to enforce stricter security policies.

cp hello hello-signed |

Test dylib injection on hardened runtime binary:

- Attempts to inject a dylib into a binary with hardened runtime enabled should fail if the dylib does not match the code-signing requirements.

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=example.dylib ./hello-signed |

- Set library validation requirement and test:

- Enforcing library validation to ensure that all loaded libraries are signed with the same certificate as the main executable.

codesign -f -s "Your Certificate Name" --options=library hello-signed |

Setting the CS_RESTRICT Flag

Setting the CS_RESTRICT flag on a binary:

- Manually setting the CS_RESTRICT flag using the

codesigncommand with the--option=0x800flag. This is not typical in standard practice but can be used to enforce stricter security measures.

- Manually setting the CS_RESTRICT flag using the

codesign -f -s "Your Certificate Name" --option=0x800 hello-signed |

Verifying the signature and the CS_RESTRICT flag:

- After setting the flag, verify that it has been applied correctly using the

codesign -dvcommand to display detailed information about the code signing status of the binary.

- After setting the flag, verify that it has been applied correctly using the

codesign -dv hello-signed |

Setting the CS_RESTRICT flag enhances security by restricting how the binary can be modified or interacted with, particularly by dynamic libraries. As With CS_RESTRICT set, any attempt to inject dynamic libraries using mechanisms like DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES will fail unless they meet specific security criteria, usually involving matching signatures.

Dylib Hijacking

Most important load commands & functions from a dylib hijacking point of view are the following:

| Command | Description | Relevance in DYLIB Hijacking |

|---|---|---|

LC_LOAD_DYLIB |

Specifies a path to a dynamically linked shared library. The library must be present for the binary to load and run successfully. | Hijackers can place a malicious dylib at the specified path, allowing it to be loaded instead of the legitimate library. |

LC_LOAD_WEAK_DYLIB |

Similar to LC_LOAD_DYLIB, but allows the application to run even if the dylib is not present or fails to load. |

Allows more flexibility for attackers since the absence of the dylib does not prevent the application from running. This means a malicious dylib can be inserted without immediate detection. |

LC_REEXPORT_DYLIB |

Used to re-export symbols from another dylib, essentially forwarding all requests for symbols to another library. | An attacker can use this command to make a malicious dylib appear as a proxy for a legitimate library, tricking the application into using it as if it were the original. |

LC_LOAD_UPWARD_DYLIB |

Specifies a dylib that should be loaded, but is typically used when two dylibs are interdependent (i.e., each relies on the other). | Can be exploited in complex scenarios where multiple interdependent libraries are involved, allowing an attacker to insert a malicious component into a dependency chain. |

Dylib Hijacking Scenarios

1. LC_LOAD_DYLIB

Scenario: An application uses a common library like libpng.dylib for image processing. The library is loaded via LC_LOAD_DYLIB with a path pointing to /usr/local/lib/libpng.dylib. An attacker gains write access to /usr/local/lib/ and replaces libpng.dylib with a malicious version. When the application is launched, the dynamic linker loads the malicious dylib instead of the legitimate one, allowing the attacker to execute arbitrary code within the context of the application.

2. LC_LOAD_WEAK_DYLIB

Scenario: A video editing software includes optional support for a plugin via a weakly linked library libplugin.dylib, referenced by LC_LOAD_WEAK_DYLIB. The software functions normally without this plugin if it’s not found. An attacker can drop a malicious libplugin.dylib into an expected search path (exploiting the weak link nature). The next time the software tries to load this plugin, it will inadvertently load the attacker’s dylib, enabling the attacker to manipulate or control the software.

3. LC_REEXPORT_DYLIB

Scenario: A system utility uses LC_REEXPORT_DYLIB to re-export libssl.dylib, allowing all symbols of libssl.dylib to be available to any module loaded by the utility. An attacker replaces the libssl.dylib with a malicious version on a system where the utility has permissions to write, or tricks the utility into loading the malicious version from a controlled path. The utility then inadvertently exports the symbols from the malicious library to other parts of the application, leading to widespread impact across the utility’s functionalities.

4. LC_LOAD_UPWARD_DYLIB

Scenario: An application uses two interdependent libraries, libA.dylib and libB.dylib, loaded via LC_LOAD_UPWARD_DYLIB. Both libraries depend on each other to function correctly. An attacker manages to replace libA.dylib with a malicious variant that still satisfies the dependency requirements of libB.dylib. When libB.dylib loads and calls functions from libA.dylib, it executes malicious code embedded by the attacker, potentially compromising data processed by libB.dylib.

5. dlopen

Scenario: A network monitoring tool dynamically loads custom extensions based on user configuration. The tool uses dlopen to load user_extension.dylib specified in a user-editable configuration file without verifying the path or authenticity of the file. An attacker modifies the configuration file to point dlopen to a malicious dylib located on a network share or a local path controlled by the attacker. When the tool executes and calls dlopen, it loads the malicious dylib, granting the attacker control over the network monitoring tool’s operations and data.

Test Apps for Dylib Hijacking

- Variables and it’s paths

| Variable | Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

@executable_path |

Replaced with the path to the directory containing the main executable. Useful for loading dylibs/frameworks within the application bundle. | Path of Main Executable: /some/path/My.app/Contents/MacOS/MyPath to Framework: /some/path/My.app/Contents/Frameworks/Foo.framework/Versions/A/FooLoad Command: @executable_path/../Frameworks/Foo.framework/Versions/A/FooThis setup allows the application directory to be relocated without breaking the path dependencies. |

@loader_path |

Replaced with the path to the directory containing the binary that includes the load command. Useful for plugins or modules with unknown final filesystem locations. | Path of Plugin Executable: /some/path/Myfilter.plugin/Contents/MacOS/MyfilterPath to Framework: /some/path/Myfilter.plugin/Contents/Frameworks/Foo.framework/Versions/A/FooLoad Command: @loader_path/../Frameworks/Foo.framework/Versions/A/FooThis allows the plugin directory to be movable without affecting the dynamic linking of embedded frameworks. |

@rpath |

A runtime search path used by the linker to locate dylibs. Multiple @rpath entries can be specified. These are usually set at compile time and can be overridden at runtime. |

Application Example: /some/path/MyApp.app/Contents/MacOS/MyAppLibrary Example: /some/other/path/libMyLib.dylibLoad Command in MyApp: @rpath/libMyLib.dylibPossible RPATH Entries: 1. @executable_path/../Frameworks2. /usr/local/libThis allows flexible library referencing that adapts based on runtime conditions or application deployment configurations. |

LC_LOAD_WEAK_DYLIB

- Test using

LC_LOAD_WEAK_DYLIB

1- First check the app/binary security and if it's exploitable |

Rpath-based dylib hijacking

1- Grep the paths where is used for loading |

dlopen dylib hijacking

the search path will default to the following (as noted at DYLD_FALLBACK_LIBRARY_PATH): |

Exploit Dylib Hijacking

- A

dylibtest code:

|

- Exploitation steps

After identifying which dylib is vulnerable, Compile the test code |

Mach IPC & Injection

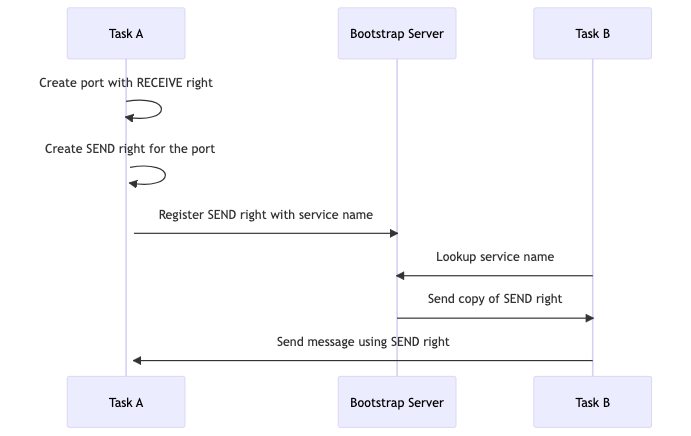

Fundamentals of IPC via Bootstrap Server

Task A Creation Steps:

- Create Port with RECEIVE Right: Task A starts by creating a new communication port for which it holds the RECEIVE right. This right allows Task A to receive messages sent to this port.

- Create SEND Right: Task A then creates a SEND right for the same port, which will be used to allow other tasks to send messages to this port.

Bootstrap Server Registration:

- Register SEND Right: Task A registers the SEND right with the bootstrap server under a specific service name. This is a crucial step as it associates the SEND right with a recognizable service name that other tasks can refer to.

Task B Lookup and Communication:

- Lookup Service Name: Task B queries the bootstrap server to find the service name. If found, the server provides Task B with a copy of the SEND right.

- Send Message Using SEND Right: Now equipped with the SEND right, Task B constructs a message and sends it to Task A using the SEND right.

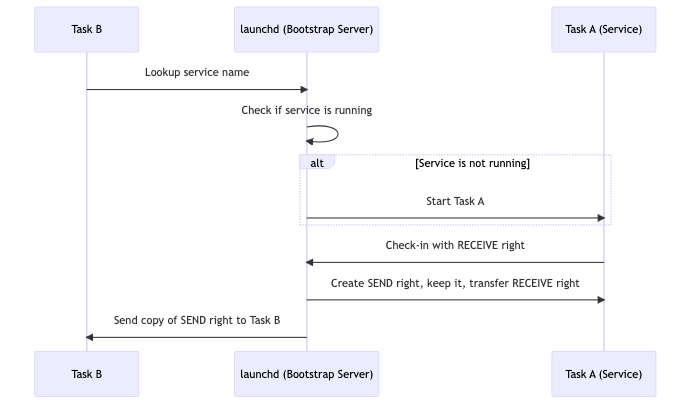

Secured Communication Model with Launchd as Bootstrap Server

Apple stores system-provided service names in configuration files that also contain the associated binary for each service. These files are located at /System/Library/LaunchDaemons and /System/Library/LaunchAgents, SIP protected locations which are considered secure.

Task B Service Lookup:

- Lookup Service Name: Task B initiates the communication by requesting a service name from

launchd. This is the first step in establishing a communication link.